Media Effects Research Lab - Research Archive

Real or enhanced? A closer look into the effects of photo manipulation

Student Researcher(s)

Anna Allsop (Masters Candidate);

Laura M. Caldwell (Masters Candidate);

Lauren J. DeCarvalho (Masters Candidate);

Faculty Supervisor

INTRODUCTION

It has been argued that the use of digital manipulation in popular media increases drive for thinness and decreases women’s sense of empowerment. This study examines the effects of image alteration on these dependent variables, using the Social Comparison Theory as a framework.

RESEARCH QUESTION / HYPOTHESES

RQ1: For women, controlling for major, gender and class standing, what is the relationship between the presence/absence of image alterations, focusing on the entire body/focusing on the face and one’s sense of empowerment?

RQ2: For women, controlling for major, gender and class standing, what is the relationship between the presence/absence of image alterations, focusing on the entire body/focusing on the face and one’s drive for thinness?

RQ3: For women, controlling for major, gender and class standing, what is the relationship between the presence/absence of image alterations, focusing on the entire body/focusing on the face and one’s perceived reality?

H1: Participants in manipulated image conditions will score lower on empowerment measures compared to those in non-manipulated image conditions.

H2: Participants in manipulated image conditions will have a higher drive for thinness compared to those in non-manipulated image conditions.

H3: Participants in manipulated image conditions and non-manipulated conditions will perceive reality differently.

METHOD

In a randomized fashion, 98 female Penn State students (both undergraduate and graduate) were asked to view one of four conditions: manipulated body images; non-manipulated body images; manipulated face images; and non-manipulated face images. They were then asked to respond to a 25-item questionnaire using scales that measured empowerment, drive for thinness, and perceived reality.

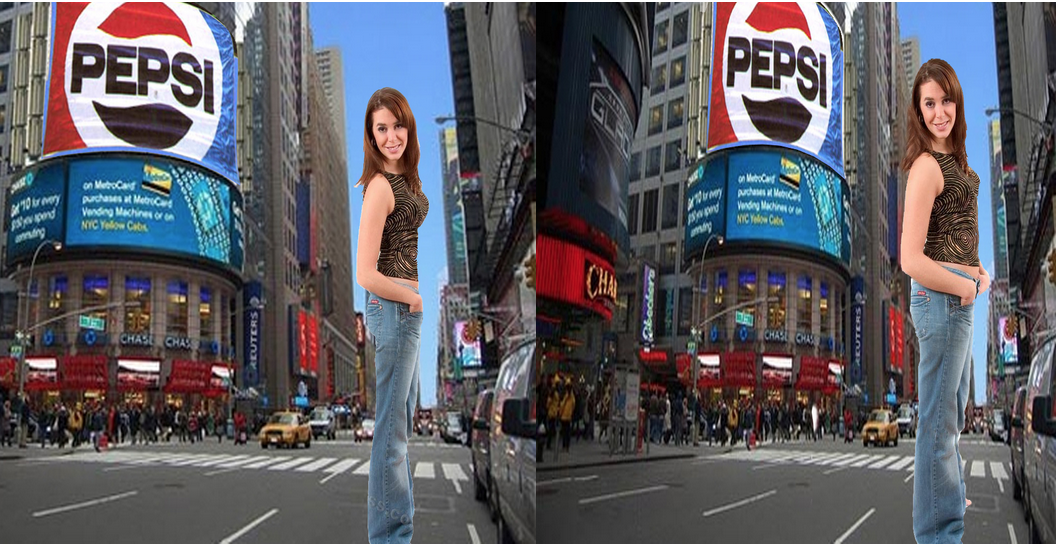

Manipulated Body Image/Non-manipulated Body Image

Manipulated Face Image/Non-Manipulated Face Image

RESULTS

RQ1: Partially answered through the findings that partially support H1.

RQ2: There was no evidence to answer this RQ due to the lack of support for H2.

RQ3: Partially supported through the findings that partially support H3.

H1: Partially supported. In terms of measuring empowerment, female participants who viewed manipulated body images were more likely to report a higher level of empowerment than those who viewed manipulated face images. In comparison, female participants who viewed non-manipulated body images were less likely to report a higher degree of empowerment than those who viewed non-manipulated face images.

H2: Not supported by the findings of the study.

H3: Partially supported. When assessing two dimensions of perceived reality as a dependent variable, specifically the perceived realness of models in ads and the perceived unimportance of attractiveness, female participants who viewed non-manipulated images were more likely to report that the models in the ads appeared to be real than those who viewed manipulated images. Additionally, female participants who viewed manipulated body images were more likely to report that attractiveness is unimportant than those who viewed manipulated face images, whereas participants who received non-manipulated body images were less likely to report that attractiveness is unimportant, than those who received non-manipulated face images.

CONCLUSION

The findings from this study suggest that the locus of manipulation (i.e. body or face) does play a role in contributing to the effects of image alteration on dimensions of empowerment and perceived reality. Specifically, in terms of these two dependent variables, the results of this study has revealed that participants who viewed either manipulated body images or non-manipulated face images were more likely to report a higher level of empowerment, than those who viewed their respective counterpart conditions (e.g. non-manipulated body images or manipulated face images). In consistency with this finding, participants who were exposed to these two particular conditions, either manipulated body images or non-manipulated face images, were more likely to report that attractiveness was not an important factor, than those who viewed non-manipulated body images or manipulated face images.

While there was no support for the effects of image alteration or the locus of manipulation on one’s drive for thinness, the findings of this study show that the locus of manipulation and the presence/absence of image alterations can separately affect one’s perceived reality, specifically one’s perceived realness of models from the ads. Participants who viewed body images were more likely to report that the models from the ads looked real, than those who viewed face images. Additionally, participants who viewed non-manipulated conditions were more likely to report that the models from the ads looked real, than those who viewed manipulated conditions. This finding indicates that participants were able to recognize when models’ faces or bodies were altered (i.e. Photoshopped), thereby looking abnormally perfect in the eyes of the average female.

For more details regarding the study contact

Dr. S. Shyam Sundar by e-mail at sss12@psu.edu or by telephone at (814) 865-2173